Shift Concussion Management Provider (Level 2)

As a Level 2 Shift Concussion Management Provider, we tailor effective concussion management procedures to persons of all ages who have sustained a concussion or mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). We utilize evidence-based concussion assessment and rehabilitation procedures to ensure that clients seeking support in their recovery receive an informed and high standard of treatment.

At Naturology Centre, we believe that managing concussions involves a multi-disciplinary approach, and we encourage our practitioners to examine and treat each patient holistically in order to tailor rehabilitative strategies to each person’s unique needs. We value our testing protocols that collect objective data on a variety of different aspects of performance and function in order to aid in the development of individualized treatment plans. We also promote open communication and collaboration with all health practitioners involved in the client’s care.

DO I HAVE A CONCUSSION?

STEP 1 – Tell someone (your spouse, coach, parent, instructor, etc.), so you don’t feel lonely. Withdraw from sports, classes, and/or employment until a physician can thoroughly assess you. Early on, rest is the best treatment.

STEP 2 – Make an appointment with a doctor as soon as possible. Unless your symptoms are severe or quickly deteriorating, you may not need to go to the ER. Get a good night’s sleep without someone waking you up. Limit phone, TV, and computer use. Do not engage in visually demanding activities such as reading or attend noisy events such as sporting events.

STEP 3 – Seek a physician’s medical evaluation. Unless a more serious injury is suspected or needs to be ruled out, this does not include CT or MRI.

STEP 4 – Contact a Shift Concussion Management Provider in your area. If you’ve already had baseline testing, repeating it will show any regions affected by the injury and may assist in early management strategy development. Untested individuals should still schedule a follow-up appointment with one of our trained practitioners.

STEP 5 – Implement your physician’s and shift concussion management providers concussion advice. Specialized rehabilitative treatments (e.g. vestibular therapy/exercises to help combat dizziness) and other healing procedures may involve physical rehabilitation (e.g., accompanying neck pain).

STEP 6 – Follow up with your providers to ensure proper recovery. Ask questions! Knowing your injury will help you heal.

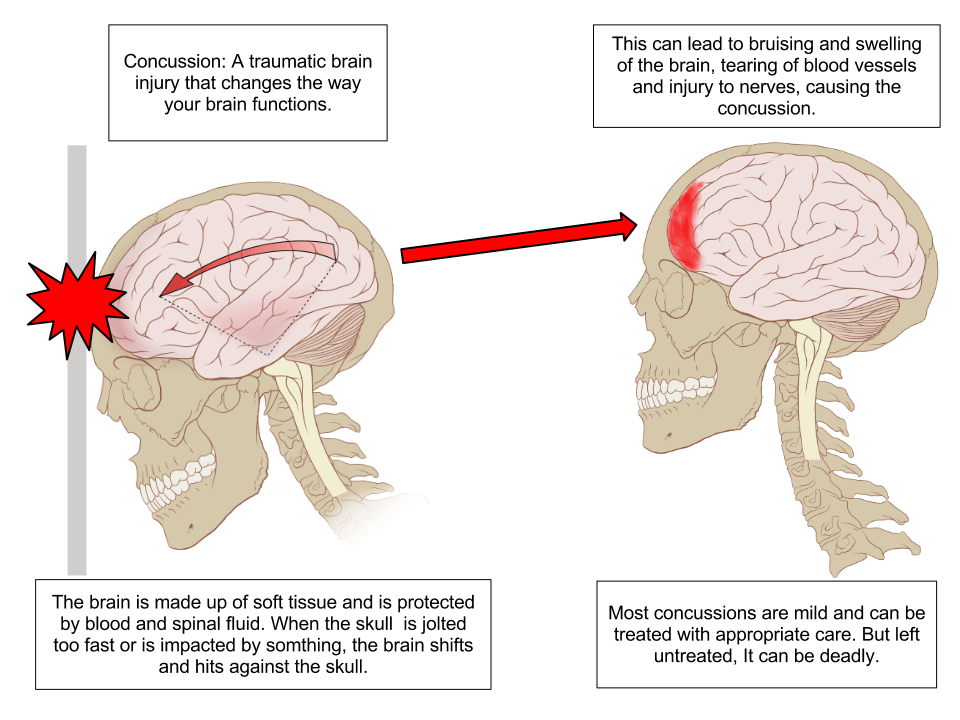

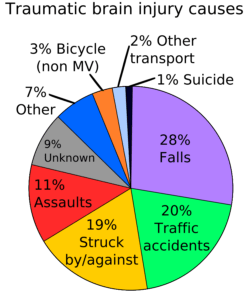

A concussion is currently defined as “a complex pathophysiological process affecting the brain that is generated by traumatic biomechanical stresses” (developed by the consensus panel at the 1st International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Vienna, Austria in 2001). Simply put, a concussion alters the way our brain processes – it makes it less efficient. It can be produced by a direct blow to the head, face, neck, or anywhere else on the body that transmits a “impulsive” force to the head. A concussion may or may not result in consciousness loss (not a diagnostic requirement). Indeed, fewer than 20% of concussions result in unconsciousness.

Several frequent symptoms associated with concussions include the following:

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Neck ache

- Vomiting or Nausea

- Loss of equilibrium

- Inadequate coordination

- Having difficulty focusing on objects or words

- Insufficient concentration

- Feeling a little “foggy”

- Confusion

- Amnesia, or a lapse of memory

- “Bright lights”

- Vision that is blurred or double

- Observing “stars”

- Irritability or a shift in one’s emotional state

- Ear ringing

- Directions are difficult to follow

- Reduced ability to play

- Distracted easily

- Vacant look

- Drowsiness/fatigue

- Difficulty sleeping

- Feeling “off” or dissatisfied with oneself

A hit to the head, face, or jaw, whether direct or indirect, can cause the brain to accelerate and then swiftly decelerate within the skull. This acceleration/deceleration motion can cause mechanical changes in nerve fibres, stretching them and altering numerous critical metabolic processes. While the injury is obvious given the range of symptoms a concussed athlete reports, routine imaging procedures often reveal minimal structural damage (e.g. CT, MRI). Rather than that, these imaging techniques are utilized to rule out more serious damage, such as bleeding within the brain or skull or skull or neck fractures. We know that just because we cannot always see the physical injury doesn’t mean it isn’t really there.

Current data suggests that when nerve fibres in the brain are stretched rapidly during a concussion, numerous neurotransmitters (brain signalling molecules) are released, initiating a complicated neurometabolic cascade. These alterations occur minutes after the injury and might linger for hours, days, or weeks before returning to normal. Eventually, an energy crisis occurs, and the brain cannot generate enough energy to sustain its usual functions. In conjunction with other compromised physiological processes, this metabolic imbalance is hypothesized to contribute to the physical, cognitive, behavioural, and emotional signs and symptoms often observed in a concussed individual.

While the majority of concussion-related symptoms are believed to recover within a few days to weeks, some may last for months:

- Certain children and adolescents

- Individuals who have sustained many concussions in a relatively short period of time

- Individuals who suffer from chronic migraine-like headaches, visual or vestibular impairment, or a high symptom burden

- Individuals with a history of migraine, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), learning difficulties, or sleep issues

Some people appear to recover rapidly, while others do not remain a mystery. Even if symptoms resolve fast, it is recommended that athletes returning to sport follow a proper progressive return-to-play strategy.

A postconcussion syndrome is a diagnostic term that refers to symptoms that remain for several weeks, if not months, following an accident. If your symptoms last longer than three to four weeks, you must have an adequate assessment (or re-assessment) to receive the appropriate information and management techniques for your illness.

Second Impact Syndrome is a rare but deadly complication of head trauma, characterized by rapid brain swelling and the potential for severe impairment or death. Second impact syndrome is debated as a result of cumulative head trauma (when an athlete receives another concussion while still suffering from the consequences of a previous concussion) or as a result of a single, moderate traumatic brain injury.

Second impact syndrome, regardless of its etiology, is a severe complication of head injury in young athletes. There should be no return to play when an athlete is exhibiting concussion-related signs and symptoms, regardless of the level of competition.

When the brain is metabolically compromised (as occurs with a concussion), it is believed to be more “susceptible” to further damage. That is, a second, relatively modest trauma to the head may result in more profound and lasting abnormalities in brain function. The physiologically altered brain is effectively weakened, making it less capable of withstanding or recovering from a later (though mild) concussion. Thus, concussive injuries are believed to be cumulative, with decreasing force necessary to inflict brain harm each time (when occurring in close temporal relation). Symptoms may be utterly out of proportion to the mechanism of harm. What would have been two “moderate” concussions combine to create a more severe traumatic brain injury with a longer duration of the damage.

Athletes frequently downplay the severity of concussion-like symptoms or fail to disclose them at all after a head injury. This could be because the athlete desires to continue playing and believes the symptoms are manageable. The athlete may believe that getting their “bell rung” is a necessary component of their performance. Often, the player, parent, coach, or trainer is unaware of the serious repercussions of playing with a concussion in these instances.

However, when a concussion is recognized early, correctly managed, and returned to sport gradually, the athlete’s risk of suffering another concussion is unlikely to be considerably different.

Concussions can be challenging to correctly diagnose due to various symptoms and individual responses (especially for the layperson). While headaches and dizziness are prevalent, they can also arise due to a range of other sports-related disorders (e.g. dehydration, heat-related illness). To further complicate matters, symptoms may manifest several minutes or even hours after the original damage.

As a general guideline, treat it as a concussion if you or your child exhibits one or more of the symptoms stated earlier and there was direct contact to the head or a “jostling/whiplash” effect. It is critical to recognize that the process of harm may be more subtle and less evident than that of a “huge hit.” An someone who is not responding normally has difficulty recalling events or words, or is having difficulties following directions, may have experienced an injury several hours ago. For athletes, regardless of athletic performance level, there should be absolutely NO return to play on the same day as the injury.

Parents, coaches, and trainers should be taught that using a symptom scale/checklist effectively identifies symptoms consistent with a concussion. For a team coach or trainer familiar with the athlete, it may be clear that the athlete is having difficulty answering simple questions and/or behaving strangely or differently. Other instances are less obvious. Sideline concussion examinations, which evaluate an athlete’s orientation, focus, and memory, aid in determining how well their brain functions. Although the Pocket Concussion Recognition Tool is an excellent sideline assessment tool for evaluating the areas above, it is not intended to replace a full evaluation by a medical expert.

Return to school or work is often case-specific and may vary according to the degree and nature of symptoms. Before making a decision, it is critical to obtain the counsel of a skilled health professional. Return to school or work is generally advised as soon as exposure to the classroom or workplace is acceptable (i.e. you do not need to be completely symptom-free). Excessive/prolonged rest at home can have several negative repercussions, including developing or deterioration of sleep habits, anxiety/depression, social disengagement, and hyper-awareness of symptoms. Initially, concessions such as shorter days/shifts, reduced workload, frequent breaks, altered job responsibilities, or temporary projects are frequently required to limit symptom aggravation. All these adjustments mentioned may not be required once symptoms have improved.

Once symptom-free, it is recommended that each athlete participates in a progressive exercise testing regimen. Like weight training, athletes recuperating from a concussion should avoid abruptly increasing their level of exertion from 0% to 100% in a short period of time. Physical exertion testing is critical not only for physical re-conditioning but also to monitor for symptom recurrence and to help avoid an early return to sport. Even if you feel fine, activities such as jogging, leaping, or stickhandling may trigger the recurrence of your symptoms.

Returning to play is a slow process. The first step often entails modest cycling or jogging to boost your heart rate moderately. If no symptoms worsen during or within 24 hours following this exercise session, you may advance to a more challenging workout regimen. Eventually, you may progress to on-field or on-ice practice and finally to full gameplay (with proper medical clearance). If your symptoms recur at any point, you must return to a lower degree of effort (or modified activities) as directed by your health practitioner.